The Future of English Language Teaching and Learning?

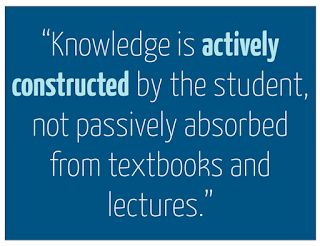

We are now used to a web experience in which we can integrate images, user-generated and personalised content, as well as the freedom to browse and search for precisely what we want. It is easy to see that this pattern of activity has not yet become part of our approach to language learning, especially if we think about the traditional school setting. Although many schools are now moving towards incorporating contemporary learning styles into their architecture, it is often not so evident in the syllabus which can remain prescriptive. There is a challenge to create an environment in which learners can determine what, how, and when they learn. From our involvement with the world-wide web we have developed critical thinking skills and we are now more used to the ideas of lifelong and independent learning. The near future should allow learners to create their own learning paths, as well as interacting easily across existing boundaries of space and time. Learning will theref